I have finished the Harvard MOOC I was taking. The course was called “Book Sleuthing: The Nineteenth Century,” and it is part of a series called “The Book: Histories Across Time and Space” that looks at the physical aspects of books rather than their content per se. The series examines books based on their paper, ink, and binding. It looks at hand-lettering and printing, as well as artwork, and it looks at who was reading the books and how.

Here’s what I learned about nineteenth-century books from Leah Price, Professor of English at Harvard. In part, it is a story about the loss of jobs for rag-pickers, who were named for their main article of trade. Before the invention of paper made from wood pulp in the mid-1800s, paper was made from used fabric, supplied to paper mills by rag-pickers who scavenged the cities for discarded clothing and other things made of cloth. Rag-pickers are still around, some of them making TV shows such as “American Pickers,” but back then, many were losing work to lumbermen. Wood-pulp paper was much cheaper to produce, and by the turn of the twentieth century, dime novels and the like were well on their way to being in everyone’s pocket or purse, possibly to the detriment of our morals, as Harold Hill warned in The Music Man.

Here’s what I learned about nineteenth-century books from Leah Price, Professor of English at Harvard. In part, it is a story about the loss of jobs for rag-pickers, who were named for their main article of trade. Before the invention of paper made from wood pulp in the mid-1800s, paper was made from used fabric, supplied to paper mills by rag-pickers who scavenged the cities for discarded clothing and other things made of cloth. Rag-pickers are still around, some of them making TV shows such as “American Pickers,” but back then, many were losing work to lumbermen. Wood-pulp paper was much cheaper to produce, and by the turn of the twentieth century, dime novels and the like were well on their way to being in everyone’s pocket or purse, possibly to the detriment of our morals, as Harold Hill warned in The Music Man.

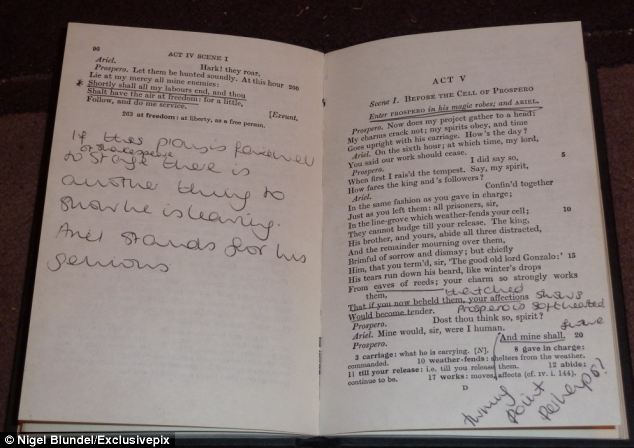

Readers also began to treat books differently. Whereas formerly only church monasteries or the very rich had libraries, gradually more common folk could own books. The golden age of “marginalia” began in the early nineteenth century when paper was still expensive, but more available to the middle class. Not only could books be read and reread (e.g., bibles), or used for reference (e.g., dictionaries, at a time when American national pride involved a divergence in spellings from those of our former English oppressors), or enjoyed by women and domestics as modern inventions such as the sewing machine gave them more free time (e.g., novels)—but also the spare paper at the margins of these books could be used for any number of purposes related or unrelated to the book itself, such as making notes on the content, practicing one’s handwriting, or writing down one’s shopping list. This marginalia is the bread and butter of a book sleuth.

Readers also began to treat books differently. Whereas formerly only church monasteries or the very rich had libraries, gradually more common folk could own books. The golden age of “marginalia” began in the early nineteenth century when paper was still expensive, but more available to the middle class. Not only could books be read and reread (e.g., bibles), or used for reference (e.g., dictionaries, at a time when American national pride involved a divergence in spellings from those of our former English oppressors), or enjoyed by women and domestics as modern inventions such as the sewing machine gave them more free time (e.g., novels)—but also the spare paper at the margins of these books could be used for any number of purposes related or unrelated to the book itself, such as making notes on the content, practicing one’s handwriting, or writing down one’s shopping list. This marginalia is the bread and butter of a book sleuth.

Ironically, cheaper paper brought about the end of marginalia, as schoolchildren were provided with textbooks to be reused the following year by the next class and they were, in conjunction with the advent of Victorian values of propriety, discouraged from writing in the books. Public libraries also boomed, and polite book-borrowers were expected to return books in the same shape they found them. Writing in books became passé and vilified. And besides, there was now plenty of cheap paper in other forms available to use for taking notes and making lists.

Cheap paper and cheap books also meant reading material could be designed to have a short life, such as newspapers and serial story magazines. This planned obsolescence contrasts with my favorite artifact shown by Prof. Price, an 1836 dictionary carried by a Union soldier in the Civil War. Yes, this man with evident plans for self-betterment took a dictionary with him to war! Just a couple of inches thick and wide, this dictionary was printed on linen paper but was intended for the already growing population of people who could afford books, though the books, well used and scribbled in throughout, were also well taken care of by their owners (or their wives) by restitching bindings and torn pages with needle and thread (which was possible because the paper was fabric-based).

Cheap paper and cheap books also meant reading material could be designed to have a short life, such as newspapers and serial story magazines. This planned obsolescence contrasts with my favorite artifact shown by Prof. Price, an 1836 dictionary carried by a Union soldier in the Civil War. Yes, this man with evident plans for self-betterment took a dictionary with him to war! Just a couple of inches thick and wide, this dictionary was printed on linen paper but was intended for the already growing population of people who could afford books, though the books, well used and scribbled in throughout, were also well taken care of by their owners (or their wives) by restitching bindings and torn pages with needle and thread (which was possible because the paper was fabric-based).

The “Book Sleuthing: The Nineteenth Century” materials only took two hours at the most to work through but the theme and details of the class gave me a lot to think about. For example, although modern books such as field guides to birds or flowers that are labeled “pocket companions” are normally too big for today’s pockets that can’t even fit our phones, which incidentally are fast becoming the twenty-first century’s form of the book, the term “pocket companion” has a legitimate history from a time when some books were literally that—intended to be carried in the pocket or purse.

A nineteenth-century word for a man’s or woman’s purse was “reticule,” and one final thing I learned from this on-line class that I will never forget is how to actually pronounce “reticule.” I have often read this word, but never before could use it in conversation. With my Harvard education, now I can!