I am 36 percent of the way through War and Peace, that is, I’m on page 444 of my edition of this book that is known for its length. Is it true that Tolstoy was paid by the word?

The fact is, I have read longer books, one being Atlas Shrugged, by Ayn Rand, which beats War and Peace by some 58,000 words. The only reason I made it through Atlas Shrugged, by the way, is that Rand was a good, compelling writer and it is a page-turner. Besides that, and except for the fascinating science-fiction elements, the book was single-handedly responsible for my high blood pressure, and I think I burned my copy when I was done. Admittedly, I should probably re-read it someday, since Rush Limbaugh and his like who were praising it so highly at the time I read it were looking at Rand’s story through the jaundiced eye of anti-socialism and not in fact commenting on Rand’s actual philosophy.

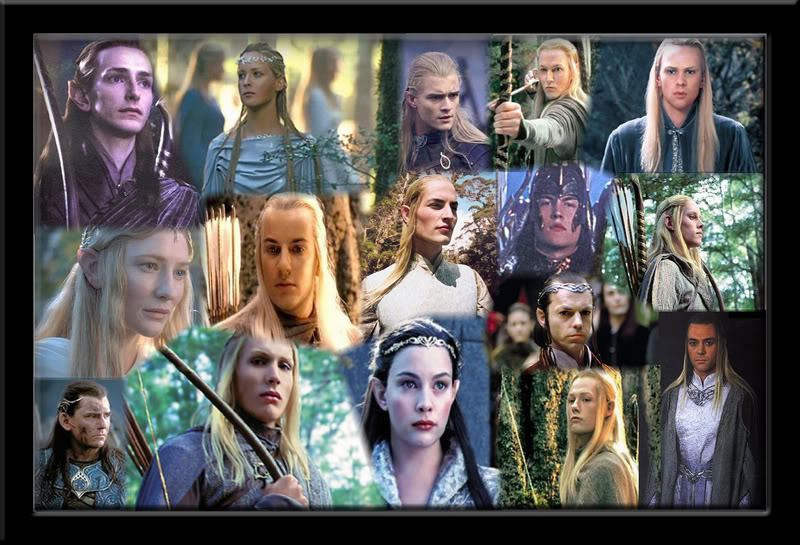

Length is not a deterrent to me in a book. My two favorite stories were written in multiple volumes (as War and Peace really is), and both are longer than Atlas Shrugged. The Lord of the Rings trilogy, my first-ever favorite book, comes in at 172,000 words longer than Rand’s tome, and I have read it seven times. My second favorite series, Steven King’s Gunslinger series, if you read all seven volumes, is about four times longer than War and Peace. I have read the first three of the Gunslinger books at least four times and the others at least once.

So, my thoughts on War and Peace so far. Someone wrote this: “The setting is elaborate and ornate, the plot labyrinthine, the adventures exciting.” No, sorry, that was written about the sci-fi novel Dune, another long book that I have read multiple times, but the three topics of setting, plot, and adventures are relevant. Keep in mind that a final word on all of my comments below is yet to come, because, as I have read, the last volume of War and Peace is very unlike the first two.

The setting of War and Peace should be elaborate and ornate, being early 19th-century Russia; but Tolstoy’s “peace” descriptions of the physical settings about which the social elite move are scarce and those that do appear are pedantic and bare—e.g., “there was a window to the right and a desk in the middle of the room.” He mentions their clothing with the broadest of strokes such as “she wore a white cotton dress.” The “war” descriptions of battlefields are fascinating in their detail but, again, are not written to awe the reader with their intrinsic drama so much as they reveal Tolstoy’s interest in the history.

The setting of War and Peace should be elaborate and ornate, being early 19th-century Russia; but Tolstoy’s “peace” descriptions of the physical settings about which the social elite move are scarce and those that do appear are pedantic and bare—e.g., “there was a window to the right and a desk in the middle of the room.” He mentions their clothing with the broadest of strokes such as “she wore a white cotton dress.” The “war” descriptions of battlefields are fascinating in their detail but, again, are not written to awe the reader with their intrinsic drama so much as they reveal Tolstoy’s interest in the history.

The story comes from elsewhere: I see the setting of the book not as a costume drama that awes us with jewels and silks and gilded architecture or horrifies us with images of war but as comprising the minds and thoughts of the characters. At revealing—in great detail—how the minds of his characters work, Tolstoy excels. When that white cotton dress is briefly mentioned, it serves as a backdrop upon which to reveal a character’s thought that she feels attractive and seductive, or plain and unloved.

The plot appears labyrinthine due to the large number of characters the writer follows slowly through the story, skipping from one character’s storyline to the other and from peace to war and back again. Yet there are fewer characters to be concerned about here than there are in the Lord of the Rings trilogy (especially if you read Tolkien’s extensive appendixes!) or in the six seasons of Downton Abbey, perhaps.

The plot appears labyrinthine due to the large number of characters the writer follows slowly through the story, skipping from one character’s storyline to the other and from peace to war and back again. Yet there are fewer characters to be concerned about here than there are in the Lord of the Rings trilogy (especially if you read Tolkien’s extensive appendixes!) or in the six seasons of Downton Abbey, perhaps.

As for adventures, they are soap-opera-ish, like those on Downton Abbey. And many if not most occur inside the character’s thoughts, without physical action, even during the “war” scenes, but they are exciting enough that this reader is willing and eager to read 64-percent more to find out what happens to each of the characters in the end.